Mary Spencer was a first rate teacher, but also a surrogate mom to many of her pupils.

All Grown Up

By Evita Caldwell

Photos By J.B. Forbes/St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Fifteen years ago developer Richard Baron persuaded civic leaders and business people to spend millions of dollars and provide in-kind services to rescue “at risk” students at the school that I attended just a mile from downtown St. Louis.

In 2000, the Post-Dispatch published a series about that effort called, “A Better Place to Grow Up.” The narrative focused primarily on long-time teacher Mary Spencer and her classroom of fifth graders at Jefferson School.

Baron’s effort was a grand experiment, full of good intentions, and I was one of the guinea pigs. Now I am all grown up and so are my classmates.

As a student in Spencer’s class, I remember the physical improvements and curriculum changes that Baron helped bring to our school. But I had no idea of the scope of the effort, nor Baron’s role in our community. What I understood was that our school had been singled out as special and that the people who came to help considered us at risk and in need of help and support.

Having a strong support system at home, I cannot say that I felt at risk. My parents had high expectations for me, and by then I had them for myself. But I did understand that not every student had the necessary foundation for success. I knew most of my classmates were performing below grade level. Later I would find that we lived in a ZIP code with the lowest average household income in the city. Nine in every 10 children were living with single mothers, and 40 percent of those moms did not complete high school, according to one estimate.

As I got older and became increasingly fixated on urban life as a field of endeavor, I came to understand that Baron and the civic leaders involved had come to “level the playing field.” They wanted Jefferson to mirror other schools that had more resources and better facilities.

You could look back and say I was a beneficiary of this largesse. But there was more to it and less to it than that. My parents and Mary Spencer were the keys to my success and they were in place long before Baron came on the scene. Academically I rocketed through a St. Louis public school system that was dysfunctional despite Baron’s best efforts. I graduated second in my class in 2007 from Vashon High School, among the worst high schools in the state. The graduate rate -- those getting a diploma in four years was just 45 percent. Among those who got to graduation day, just 40 percent went on to a four-year college program.

I was one of them. I qualified for a grant and I went out on a financial limb using a student loan to pay for my education at Saint Louis University. I graduated in 2011 with a degree in communications.

When I came to this story I was just barely making a living, working as a pharmacy tech at Walgreens. I contacted Richard Weiss, who wrote the original “A Better Place to Grow Up” series, to see if he could help me land a job in journalism. He suggested that as a way of demonstrating my skills to a future employer we work together on a follow-up. We would call the new series “All Grown Up.” With his coaching and editing, I would try to find my classmates from Jefferson and learn how their outcomes compared with mine. Did they live up to the dream that Richard Baron had for them? More important, did they fulfill the hopes and aspirations that they had for themselves?

When I embarked on this journey, a sense of excitement filled me, and then quickly a sense of dread. I was excited with the idea of catching up with my classmates. At the same time, I feared that many might have lived up to the stereotypes that people outside our enclave carry – that my peers got pregnant as teenagers, or joined gangs, dropped out of school or were victims of street violence.

I wondered if perhaps I was the exception to the rule. I had walked through life defying expectations. When college classmates learned where I had come from – inner city St. Louis, Vashon High – and saw a well educated, articulate woman, they often asked me, “How did you do it?”

I used to wonder why people asked me that. But, as I grew up, it became clearer.

Coming from an underperforming school and school district, my peers at Saint Louis University and new acquaintances automatically considered me educationally “inferior.” They had a right to that perception. The statistics demonstrate that children in the St. Louis school system are far less likely to graduate, go to college and earn a degree than their peers in affluent areas.

So, what’s being done to level the playing field? What’s being done to make sure that children in underperforming schools can catch up? How can we make sure that all youth receive top-tier educational opportunities? What can we learn from Richard Baron’s efforts that can be applied today?

A spoiler alert. Baron’s effort fell short of its goals – at least statistically. And, of course, it’s difficult, if not impossible to tell whether those efforts had a profound impact on any given child because so many other factors come into play in that child’s life. But Baron and other civic leaders sure did give it a go. From 1999 to 2007, Baron and his allies expanded the mission to 10 St. Louis public schools, creating the Vashon Compact. They spent millions. But the project did not work as he had hoped and the compact dissolved. To his credit, the man has never given up, and he embarked on fresh initiatives that offer new hope and promise. I have looked into that as well.

But my first job was to find my classmates. I did so by using social media, extensive research through Missouri courts, online searches and hearsay. I did not find nearly as many people as I would have liked. But among the handful that I did locate, I believe I was able to capture the essence of our experience at an urban city school, where hope and promise went to war with failure and despair. I hope everyone can learn from our journey.

The Six of Us

What happened to those of us who in 1999-2000 were in fifth grade teacher Mary Spencer’s orbit and launched to points then unknown? Well, if you go by the experiences of Bre’ Ann Jones Johnson, Kiauna Jones, Howard Small, Raymond Webber, Ashley Westbrook and me, we all landed on our feet, though not entirely without bumps and bruises. We are all taxpaying citizens. Three of us are parents. One of us is married. Two of us live in St. Louis County. Three live in the city of St. Louis, and one in Augusta, Ga.

We are a small sample. Mary Spencer touched at least 30 students in some way with her instruction and discipline that year. But I could not find them all. The St. Louis Public School District is dysfunctional in so many ways. One of them is apparently in keeping records regarding who passed through the system and how they fared afterward. Other districts keep in touch with their alumni for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is to understand how well the districts are doing in helping their students go on to successful lives. Knowing where your alumni are can also be useful in attracting support -- financial and otherwise -- for the current generation of students. Bottom line: St. Louis Public Schools were unable to help us find Mary Spencer’s kids.

If there was a star in that first set of stories about Jefferson School, it was Howard Small. Bright and outgoing, but undisciplined and brash, Howard was portrayed as the canary in the coalmine. He was the quintessential at-risk kid, an underachiever but one with a great deal of potential.

“I was just hard-headed,” he said, smiling and shaking his head as he reminisced while sitting at his dining room table in an apartment in St. Charles County. “Hard-headed and spoiled.”

Howard’s last name is apt. He is diminutive. He sometimes used that to his advantage. He was quite adorable, knew it and, as a result, could get away with doing less than his best. He was also athletic; a great tumbler, and later in life he would prove to be an elusive running back and a star on his high school football team. But because of his size, he was a target for bullies and he carried a bit of a chip on his shoulder.

Feeling like he had to prove his manhood, Howard said he began affiliating with gang culture. He got in trouble a lot; he once even got shot. He fathered two children and got hauled into court over an alleged failure to provide child support. He lived up to all the stereotypes we have for inner city children. And yet, Howard is now engaged to be married. He is holding down two jobs and has worked out his child support arrangements. His apartment is full of books that he avidly reads to his kids and his fiancée’s two children.

Looking back, he remembers that his fifth grade year with Mary Spencer as pivotal, a touchstone, that helped him find his way out of the mess that his teenage years and young adulthood had become. Somewhere in the back of his mind, he said, he knew he had to become the solid citizen that Mrs. Spencer expected him to be. You could not let her down.

Howard remembers at least vaguely all the corporate and civic support for his school. If you were to piece together his day-to-day activities, you could appreciate that this support provided Howard with after-school activities he might not otherwise have found, helped him become computer literate, and to stay at least on grade-level with his reading through a special program called Success For All.

But what he appreciated most were not the programs, but the teacher.

“She ran by the school criteria, but she twisted it a bit,” Howard said of Spencer. “We were more than just students to her. We were like her kids and grandkids. She would tell you, ‘I taught your mama, daddy, your cousins’… All these generations this lady has pushed is just amazing.”

“My life could have turned out a whole lot totally different if Mrs. Spencer had never been there [for me],” he said.

So, what does Howard think about the millions of dollars invested by civic leaders into Jefferson School and the students?

“The money didn’t mean nothing,” he said, “compared to Mrs. Spencer.”

"We're Not Ghetto"

There is no question that Mary Elizabeth Bond Spencer is unusual, if not entirely unique. She spent her entire teaching career – 41 years – at one school, Jefferson. She started on Sept. 6, 1960, the year the school opened. Though the school stood in the shadow of the Pruitt-Igoe and Vaughn housing projects, which would become notorious, Spencer said Jefferson students got a first-class education. Spencer recalled that then-superintendent Samuel Shepherd Jr. would single out the school for having the best test scores and most innovative programs.

Many teachers and a whole lot of principals moved on from Jefferson when times got tough, but Spencer stayed. That, of course, is how she was able to tell her students that she taught their grandmas and grandpas, moms and dads, aunts and uncles. I remember the minute we walked into her classroom that we were expected to perform … not just as students, but as properly behaved children. “I’m the momma,” she told us. “I have a loud voice. If I call you, you stop and holler, ‘Ma’am!’ You come and see what I want. Do you understand me?”

To which we would all answer in unison, “Yessss.’’

“We are high class,” she told us. “We’re not ghetto.”

We are not ghetto. That phrase … well it’s haunting. As proud as we were of our school … we were taught to call it THE Jefferson School, to distinguish it from all others … many of us lived under the illusion or delusion that St. Louis County was the Promised Land. Many times through my primary and secondary years friends and teachers asked why a smart kid like me wasn’t attending a magnet or county school. They would say, “You are too smart to be at Blewett, [the middle school across the street from Jefferson] you should be in a county school.” Or “you need to be somewhere else other than Vashon…. somewhere you can be challenged.”

I would tell them, “I applied. It just didn’t work out.”

My peers and their parents often referred to county schools as “white schools” even though many are quite diverse, thanks in part to the area-wide desegregation program that got started well before I was born. Many of my friends’ parents would boast about their children’s “white” school and how much nicer they were than the schools their kids previously attended. More important, they insisted they were learning so much more.”

My friend, Kiauna Jones, attended one of those schools. After leaving Jefferson, she transferred to the Rockwood School District. If we had taken a vote in Mrs. Spencer’s class on who was most likely to succeed, Kiauna probably would have won hands down. Smart as a whip in subjects like math, an incredible reader and a snazzy dresser, Kiauna exuded confidence and charisma. She knew how to put first things first and those were her studies.

By transferring to Rockwood under the desegregation program, Kiauna and her mom figured she would benefit from better teachers. There would be more resources in every classroom and she would be part of an entirely different community where just about every kid was going on to college. They figured that was well worth the long bus trip from Kiauna’s rent-subsidized townhouse in Carr Square Village to Rockwood South Middle School, way past Interstate 270 and about as far south and west as you can go and still be in St. Louis County.

“The trip was an hour,” Kiauna recalled, “and I am looking at these buildings on the way to school and saying to myself, ‘It’s big, the world is really big!’”

The experience wasn’t just a revelation to Kiauna, it was as well to the kids who lived out that way. “A lot of them had never met a city girl,” Kiauna said. “They were different to me and I was different to them back. They expected me to come there just as dumb as a doorknob, big earrings, popping gum … and starting fights. And I wasn’t.”

Kiauna became an honor student at Rockwood South and then at Lafayette High School. She lived up to all the expectations her parents and teachers had for her.

Until one day she didn’t.

In her sophomore year, Kiauna got pregnant.

Angered, Kiauna’s mother decided Rockwood was not the promised the land but a place where she encountered some bad influences. She took Kiauna out of Lafayette and enrolled her in Sumner High School back in the city.

Kiauna described her time at Sumner as the worst year of her life. “I felt out of place,” she said. “I wasn’t used to the metal detectors and the frequent fights. It was scary for me.”

Kiauna doesn’t blame her mother, but she decided that she had to take responsibility not only for her child, but also for her education. She did not revert to the stereotype. After the year at Sumner and after adjusting to child rearing, she launched a campaign to be readmitted to Lafayette High. That took some doing because she was told she would have to go to the back of the line when it came to being admitted to the program.

“I called the principal at Lafayette numerous times, wrote letters to the district explaining my case and how I excelled while attending the district,” Kiauna recalled. “I mentioned my honors recognitions. I did everything in my power to make sure my high school graduation was at home – Lafayette.”

Kiauna realized her dream, graduating from Lafayette in 2007 with a high GPA and “bragging rights.”

Looking for a happy ending here? Well yes… and no. Kiauna had a few more ups and downs in her life, but found gainful employment and settled into a nice lifestyle in north St. Louis County with her daughter, Kyla, 9, and her 3-year-old son, Ayden Manuel. But it didn’t take long before Kiauna noticed something amiss at Kyla’s school in the Riverview district. Her class “would sit up and color all day,” Kiauna recalled. “I would ask her if she had homework, and she’d say, ‘No, we don’t have any homework.’”

The Riverview Gardens School District lost its state accreditation in 2007, and beginning in 2013 Kyla and hundreds of other students could transfer to another district. The accreditation issues and the looming transfers of students not just from Riverview Gardens but also Normandy caused an uproar in the region. There have been no easy answers, but there has been lots more discussion about what civic leaders and policymakers can do to level the field in education.

And doesn’t that sound familiar?

Given her experience, Kiauna knows it isn’t just about moving from one school to the next. It’s about giving your child a sense of possibility and finding teachers – like Mrs. Spencer – who will do the same.

“If I make Kyla feel close-minded about her education, she’s going to feel close-minded about her future,” Kiauna said.

Kiauna says she hardly remembers her fifth grade year at Jefferson school, except for her friends. “I do remember Mrs. Spencer,” she said. “I still apply the lessons she taught us to my life today.”

Sadder But Wiser

Richard Baron probably never met Kiauna, though he may have passed her in the hallway or watched her perform with her classmates on one of his many visits. But I like to think he had her in his heart when he set about trying to make a difference in the lives of my classmates many years ago.

We didn’t think much about the man we knew as Mr. Baron back then. We just knew him as one of the suits who showed up now and then to see what was going on, to take our collective pulse. I am sure we were told at some point and in some way what his efforts were all about, but it went right over our heads. We were more interested in each other, having fun and doing what we could to stay out of trouble or not get caught if we did get into trouble. Basically, just like kids everywhere.

Most of us didn’t feel at risk, because we felt loved by our parents, by Mrs. Spencer and lots of other teachers.

But Baron knew better. We were at risk if you look at the numbers. A “report card” produced by Jefferson from the 1998-99 school year showed that only 27 percent of Jefferson’s 369 students were reading at grade level. Half of my fifth-grade class the following year was reading at a second- and third-grade level.

In the 1998-99 school year, 67 suspensions were issued lasting from one to three days. This is for grade school kids, not teenagers. If you live in the county, ask yourself if you know of a grade school child who got suspended for even a day.

Still, we thought we were living pretty normal lives. Most of us didn’t find enough trouble to get suspended. Most of us had parents who took good care of us. But many of us were falling behind and didn’t really know it. Though he was perceived as an outsider, Baron was no stranger to the neighborhood. I learned this in an interview we conducted at his office last year. Baron is chairman and chief executive officers of McCormack Baron Salazar, a firm that specializes in developing housing in underserved neighborhoods. Two of McCormack Baron’s developments – O’Fallon Place and Murphy Park – surround Jefferson School. So you can see why he took an interest in Jefferson and other schools nearby.

Baron believed that schools are crucial in developing strong families. Good families are the bulwarks of great neighborhoods. I didn’t know it at the time, but when Baron approached the St. Louis Public School system with plans to reinvigorate Jefferson School, he was met with some resistance and suspicion, not just from school officials, but from teachers and residents. Few people want to hear that they are falling short – even if it’s not their fault. And here was a white businessman with a financial interest in the neighborhood delivering that message.

Baron’s vision for school reform extended well beyond Jefferson. He started with Jefferson but then with other civic leaders and business people created the Vashon Compact in 2001, so called because it addressed the needs of the elementary and middle schools that funneled students into what was then the new Vashon High School.

Civic participants in the compact poured $40 million into those schools from 2001 to 2006. Jefferson got $4 million in upgrades. On the roster of supporters were companies like Anheuser-Busch, Bank of America, Edward Jones, Express Scripts, Energizer Holdings, Laclede Gas, to name just a few. The stakeholders believed that if they could make the compact work, perhaps the community would learn how to fix the entire school district. And if that happened, all of St. Louis could prosper.

Now you would think if some people came bearing those kinds of gifts, it would all go relatively smoothly. Not so.

Bill Carson, executive director of the compact, worked closely with Baron on the project. He is an African-American with a long record of working on urban issues. Still, he said, the organization ran into a raft of unanticipated problems. The compact members “didn’t know just how severe the issues were with student performance” at the target schools, he said. Beyond that he described a mistrust between school board members and the compact.

Carson said some in the district developed conspiracy theories. One was that the Vashon Compact was “an effort to take over the schools and improve them so that ‘they’ can push all of the black people out, and move all the white people into north St. Louis.”

Such theories abound. And not just in regard to Richard Baron. Many residents are suspicious of developer Paul McKee’s Northside Regeneration Project that at least on paper seems to be even more ambitious and costly than the Vashon Compact.

It should also be remembered that Jefferson School is just a stone’s throw from the old Pruitt-Igoe site. That project was supposed to provide superior, low-cost housing but in a decade became so degraded and crime-infested that the government imploded the buildings. The site never got redeveloped and remains a gated-off lot where weeds grow into trees. Given that context, could you blame residents for mistrusting the intentions of outsiders who say they are coming to help?

In an epilogue to the community in 2010, the compact administration neither claimed an outright victory, nor acknowledged defeat. But clearly if the compact had succeeded, it would have continued to this day. And it has not.

The epilogue was candid in admitting to “challenges,” including,

• Poor alignment at every level between the school board and mid-management, school to school, and principal to teacher.

• Leadership instability, including 17 board members occupying seven seats over the five-year period; six superintendents in 3 1/2 years; 23 principals over five years, and “an endless revolving door of middle-managers.”

• School closures. Four of 10 schools in compact were closed.

• Politics, entrenchment and bureaucracy.

Compact administrators admitted that they were naïve, “had no idea of the issues,” and did not “fully leverage our civic influence.”

Still the compact claimed to have accomplished “the majority of what we set out to do.”

Hundreds of students received a better foundation; schools got state-of-the-art technology; teachers and principals got training, which could be applied at whatever school they found themselves; and everyone got a deeper civic knowledge of education issues.

I think that translates to sadder but wiser. One troubling aspect for those who are sadder: Could they ever be persuaded to again back a broad-based effort to help school children? While the Vashon Compact fell short in many respects, what would have happened without it? Things could have gotten worse.

And at Jefferson School they did. After principal Anne Meese and Mary Spencer retired, several other teachers left as well. Between 2003 and 2009, Jefferson students saw four different principals. Test scores fell and enrollment dropped, according to figures compiled by the Missouri Department of Secondary and Elementary Education. In 2006, Jefferson classrooms were filled with 436 students, according to the state. But by 2011, enrollment fell to 197. At the same time, disciplinary incidents increased from 1 per 100 students in 2008 to 2.5 by 2011.

No one can say for sure that continuing the Vashon Compact would have prevented this. Jefferson was part of a school system in distress. Parents were losing confidence in the schools overall and Jefferson was just one of many subject to budget cuts, turnover and bureaucratic upheaval.

“What [the Vashon Compact] was fighting was the fact that the city schools were losing teachers and their families to the more affluent school districts, Clayton, Ladue and Parkway, ” Baron recalled.

“We were training and doing in-service,” Baron said, “and just about the time we would really get some outstanding performance and started to see kids really improving… the teachers would be gone [to another district]. It was frustrating, to say the least.”

Chris Lee, former director of external affairs at Southwestern Bell and partner in the Vashon Compact, felt the frustration as well. Lee’s SBC Communications (formerly Southwestern Bell) contributed $750,000 to help blast Jefferson School into the new millennium by wiring the school for new computers and the Internet

The disconnect, according to Lee, was mostly that the school district just didn’t trust businesses to do what was right for education.

“In hindsight,” Lee explained, “before the compact was announced, there should have been more groundwork in getting the district to buy into what the corporate and foundation community hoped to accomplish, as opposed to here we are outside of the education community telling you what you should all do with this money.”

None of this, of course, meant much to those of us who were then adolescents. We were driven day to day by Mrs. Spencer’s expectations and demands and, of course, our parents’ as well. And that brings me to my former classmate and friend, Raymond Webber, who couldn’t tell you one thing about the Vashon Compact, but can describe in three words what put him on a path to a college education and a promising future.

Mom and Dad.

Three Strikes And You’re Out, Even If You Are A Football Player

Raymond Webber grew up wanting to be a football player.

In some ways, that made him more “at risk” than other kids at Jefferson School. Many black boys from the inner city have hopes of being a professional athlete one day. And most never make it. And when they don’t, then what?

Raymond’s mother and father knew the risks. The two are divorced, but each has been a major force in their children’s lives. Raymond is the youngest of three children, all of whom are college graduates. His eldest sister, Kiara, has two master’s degrees. Kymm is finishing a master’s degree.

“My mother taught me that my success was based on what she called a ‘three-strike rule,’” Raymond said. “The first strike was that I am a male [from the inner city]. The second was that I’m black. And the third strike was up to me. I could use the first two strikes as an excuse to fail, or I could take control and do what I needed to do to succeed.”

Raymond and his family grew up on Hebert Street in the historic Hyde Park neighborhood of north St. Louis. Although the area has seen some redevelopment over the past decades, it is pocked with blighted and vacant homes. Raymond’s parents knew they had to keep him and his sisters focused and disciplined.

Raymond’s dad, Baby Ray, as he was named by his parents, though he is anything but small, served as a city firefighter and is now retired “He was so big, and I was this tiny dude looking up to this big 6- foot 1-inch man… I never wanted to be in trouble,” Raymond said.

“Even though my father didn’t live in the home with us, he still provided for us,” Raymond said. “He taught me a lot about being a man, and that if certain circumstances don’t work out, then you still have to do what you have to do to adjust.”

Raymond’s mother, Lisa Ross, by contrast is petite, but no less a force. She worked at a nearby YMCA where she got to know lots of kids and their parents. She was active at Jefferson School and in her neighborhood.

Ross appreciated what civic leaders were trying to do at the school but she said the primary responsibility for any child’s success is up to the parents. And parents in her neighborhood help each other out, creating their own support system and safety net for their families.

“Everybody around here, we know each other,” she said. “We all work together. When something goes wrong, we help each other. During the ice storm in ’06, we were running extension cords to each other, and checking on each other like, ‘Are ya’ll good? We got the grill going, we got some warm soup.’”

“When it came to report card day and the PTO, these parents came out. The kids had all types of support. The teachers and parents worked hand in hand together. If the parents were on drugs, the grandma would take care of them. They went to schools clean. You didn’t have kids coming to school hungry.”

Ross maintained that the support system was in place well ahead of the Vashon Compact. If there was a disconnect, perhaps it was that the outsiders -- the do-gooders – saw the glass half empty. They didn’t always take notice or show appreciation for the teachers, parents and grandparents who were going the extra mile to support their kids. Sometimes reformers try to fix what’s not broken.

Raymond said that when his parents weren’t watching, he knew “Big Mama” Mary Spencer was. The term “Big Mama” is a popular reference in African-American culture for the female elder of the family. Everybody loves and respects “Big Mama.” She’ll put you in check if nobody else will. But she’ll love you like no other, too. Most of all, you don’t want to do anything to disappoint “Big Mama.”

As for matters outside of school, Ross felt it was important for Raymond to stay busy. Raymond played football for the community’s little league football team, City Rec, and during his high school years while at Cleveland JROTC and Career Academy. He also took a job at the White Castle down the street.

But education always came first. If that suffered, Raymond knew football could be taken away.

After being scouted by college football teams during his high school career, including the University of Missouri, Raymond enrolled at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Raymond made a name for himself there, breaking records for the most receptions and the most yards in a game and season. He joined Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, and he majored in business marketing.

Then the dream came true. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers signed him as an undrafted free agent in 2011. A hamstring injury in training camp forced him to the sideline. In 2012, he joined the Jets and later got a tryout with the Miami Dolphins. Then it was on to the Canadian Football League, but he didn’t stick. Now he is under contract with the Arizona Rattlers in the Arena Football League. Maybe he will make it. Maybe he won’t.

Always, there has been Plan B.

B as in Business.

Raymond currently works in management training at Murphy Oil Co. outside Augusta, Ga. He plans to open a business one day that will cater to young athletes in St. Louis.

He also spends his days taking care of his 7-month-old daughter, Kylee, and her big sister, Jada, 7.

“My kids are achievers,” Ross said. “I tell them all day long that there is nothing that you can’t do. If you want it bad enough, you’re gonna do it,” Ross continued. “And if you do it the correct way, you’ll appreciate it.”

Be the Change

By 2011, I was well on my way to a college diploma and so too were my former classmates, Bre’ Ann Johnson and Ashley Westbrook. Neither Bre’ Ann nor Ashley considered themselves “at risk.” Bre’ Ann’s eyes widened with surprise when I introduced the term to her.

“Really?!” she exclaimed when I described to her what Richard Baron and other civic leaders were trying to do at Jefferson to improve outcomes.

Bre’ Ann had thought Jefferson was simply getting necessary upgrades provided to all schools. But then Bre’ Ann grew up in a financially stable home with both parents present. And after Jefferson, she got the best of what the St. Louis Public Schools had to offer. She tested for the gifted program and was accepted into McKinley Classical Leadership Academy and went on to the Gateway Institute of Technology (now Gateway STEM High). “I was probably the only person from Jefferson who went to McKinley,” Bre’ Ann told me during a visit to her home in the Penrose neighborhood in north St. Louis. “A lot of people who went to McKinley came from Kennard (the elementary school for gifted students), so I didn’t know anybody. I mean, it was weird I had to put myself out there.”

Bre’ Ann said the magnet school experience challenged her. She had to step up. “Coming from Jefferson I felt as though I really didn’t have to study because I could naturally regurgitate information. A magnet school required more of a critical thinking aspect. That was hard for me to wrap my head around.

“I feel like magnet schools were the places that were optimal learning environments for students that actually wanted to learn and were eager to increase their intellectual capacity. It was both challenging and demanding.”

Bre’ Ann also had the benefit of learning in diverse classrooms. That helped her prepare for Rockhurst University in Kansas City.

On the other hand, I had sat in classes made up entirely of African-Americans. When I attended Saint Louis University, I suddenly found myself a minority and at times self-conscious and timid, afraid to speak up. At other times I wondered whether I was living up to expectations without really knowing what the expectations were.

Ashley Westbrook’s journey was similar to mine except that it took a detour. After leaving Jefferson, her parents enrolled her in Central Catholic St. Nicholas School and Academy at 1106 North Jefferson Avenue. The school was not far from Ashley’s home, and though the racial makeup was much like Jefferson’s, Ashley’s dad believed it was a cut above Webster Middle, the school where she otherwise would have ended up. Ashley didn’t find St. Nick all that wonderful, but was looking forward to moving on from there with the friends she had made to Cardinal Ritter Prep, a parochial school with an outstanding reputation.

But just a few weeks before the start of high school, Ashley’s parents told her that she would not be going to Cardinal Ritter. They could not afford the tuition. Instead, Ashley would attend Vashon High School, just like me.

“I cried when my mama told me that I had to go to Vashon… I mean, I was bawling,” Ashley recalled.

I was secretly a little excited to have my best friend back at school with me. Just as she had grown accustomed to private school life and with high hopes of continuing through high school, it just seemed unfair. Her family wasn’t poor enough to get a substantial scholarship, but they certainly were not rich enough to pay much out-of-pocket. We also knew (or assumed) that she would lose the prestige and networking opportunities that come from attending a private school. You could almost hear doors slamming shut.

Though she didn’t anticipate it at the time, an opportunity beckoned at Vashon. Maybe here is where we can see a direct result when civic leaders extend a helping hand -- but not in a way that you might expect.

In 2004, members of the Vashon Compact got in touch with College Summit, a national program designed to help underserved students prepare for a college education. The program got underway at Vashon and other city high schools in 2005. In 2006 Ashley was in the second group of students to receive counseling and mentoring that would help them prepare for college.

Truth be told, Ashley was headed for a university anyway. Nothing was going to stop her. And she didn’t much care for the mentors; they didn’t seem as engaged or interested as she would have liked. She also thought that the program wasn’t ambitious enough, working with students like her who were college bound under any circumstance.

But instead of shrugging her shoulders and moving on with her life, Ashley decided she would personally address the situation.

After completing her freshman year in college, Ashley volunteered to become a Summit mentor. Ashley served three years in that capacity and worked hard to be a role model for her high school seniors and to give them a sense of possibility. She also grew increasingly comfortable with the program overall. She could see that the organization was beginning to reach students who would not otherwise go to college. If you visit the College Summit website, you’ll find that the program is now in 14 area high schools and has reached 12,500 students.

In this small way, one of the Vashon Compact “guinea pigs” was showing her handlers how to get it done.

Today, Ashley works at the St. Louis County Highway and Transportation Department as an office service representative. At the same time, she is working toward a master’s degree in human resources at Webster University. She plans to graduate in 2017.

What Goes Around

Though the Vashon Compact has long been out of business, programs that it brought to St. Louis Public Schools endure. One, as mentioned, is College Summit. The Center of Creative Arts, which provided programs that I enjoyed, has gotten even more active in Jefferson. In fact, Jefferson was designated an art-integrated themed school in 2009. Students received in-classroom support from 30 local arts organizations including COCA, Metro Theater Company and Springboard. The district says the collaborations use the arts to engage students in core subjects like English and mathematics.

Another is Teach For America. At a time when the district was struggling to retain talented teachers, TFA provided a cadre of young, energetic and idealistic teachers to the schools. This year Teach For America placed 89 teachers in 43 city schools. Each year, some teachers move on to other fields and careers; some decide teaching is their calling. Forty-eight TFA alums are still working in the city schools.

One of them is North Carolina native Nathalie Henderson, 34. Henderson arrived in St. Louis in 2003, Teach For America’s second year here. She moved on a very fast track, teaching at Sumner High for two years, then serving as a principal intern at Beaumont High School, and as an assistant principal at Blow Middle School and McKinley Classical Leadership Academy. In, 2009, and at age 28, she was named principal at Jefferson School. Her tenure marked at least for a time the end of the revolving door at Jefferson. And as noted, attendance dipped and performance declined.

Henderson did not work miracles immediately. She had to win the trust of parents and teachers. She had to get the students refocused on learning.

All was going well when a crisis erupted in the winter of 2013. A sixth grader brought a gun to school. Coming just a couple of months after the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Conn., the incident caused a tempest locally and even made the national news. Some parents refused to send their kids to school for the next several days. Some suggested the school ought to have children pass through metal detectors.

Henderson worked even harder to engage parents and to assure them that the incident was an aberration. Metal detectors would have sent the wrong message, she said.

An even bigger confidence builder was that for the first time, Jefferson reached full accreditation. (The St. Louis school district is provisionally accredited by the state, but the district also keeps track of each school, designating each as unaccredited, provisional, accredited and distinction.)

Reaching accredited is a huge source of pride. But so too are all the outreach efforts going on at Jefferson.

“I tell my teachers that we are more than a school here at Jefferson because of the kids that we serve and the neighborhood that we’re in,” Henderson said. “You just have to do those [extra] things.”

Residents and parents who don’t have a high school diploma can take GED classes at Jefferson. The school provides clothing and toiletries for families in need. Students can receive free dental care, participate in art therapy, and are encouraged to keep “emotional journals” for dealing with the effects and/or trauma that happens in the neighborhood.

“I think some people [have] the mindset that an education should just be about educating,” Henderson said. “But you can’t educate somebody who has these other needs as well or you’re not going to educate them well.”

She says the staff is eager to maintain Jefferson’s upward trajectory. “In the last couple of years, we have made some significant academic improvement,” Henderson said. The staff “is hungry to prove that we can do that consistently.”

Henderson’s mother is a teacher and so was her grandmother. She grew up in a middle class home and went to a suburban school, which in a counter-intuitive kind of way makes her all the more passionate about urban education.

“It just doesn’t make sense to me that based on where you live, you would get a crappy education,” she said. “I recognize I was very fortunate in my upbringing and experiences that I had. And I feel like, ‘Why can’t my students have all that too?’”

Alas, the 2014-15 school year was Henderson’s last at Jefferson. She has accepted a Teach For Teach For America School System Leadership Fellowship and will be working with principals across the St. Louis Public School System. She's on track to someday be a superintendent.

Replacing Henderson and keeping her good work going will be a significant test for the St. Louis Public School District. Everyone wonders whether the district can finally get its act together. Or will it always be one step forward -- as at it was at Jefferson when I was there -- but then two steps backward.

I posed that question to Superintendent Kelvin Adams in an interview at the school district headquarters. It would have been interesting to see how Adams might have worked with the Vashon Compact. Adams was hired in 2008 and though he has gotten mixed reviews for his work, he has stayed at the helm now for a good long time and no one is calling for his head.

Adams is familiar with the goals and aspirations that compact had and said he has learned lessons from it. Despite falling short, the corporate community remains interested in St. Louis Public Schools, he said. But he said the terms need to be different.

In the past, corporations would often come with their money and their own ideas about how it ought to be spent. Adams says the district now needs to forge its own vision, then ask civic leaders to get on board.

“There are about three or four areas that we think are important -- early childhood education, college and career focus, health and wellness…”, Adams explained. “So what we do now is ask the business community to support those things.”

“Sometimes,” he acknowledged, “we get to a point of conflict when sometimes those interests that the business community might have don’t necessarily match with our interests. But, then we’ll try to find a way to see how they can match. [And] sometimes we say, ‘No, this is not the best opportunity for us at this time’.”

Currently, the corporate community assists the district in a variety of ways. For example, Adams said that Wells-Fargo “adopted” Vashon High, Dunbar Elementary, and Carr Lane Middle schools to help with tutoring.

The Next Generation

Whatever the impact of the Vashon Compact, there’s one thing that can be said about its founder: He never quits.

Fifteen years ago when Richard Baron was just getting started with the compact, he was already looking beyond it. His dream was to build an early childhood center right next door to Jefferson School. It took nearly all of those fifteen years to get it done.

Fortunately, he found a willing and enthusiastic partner in Dr. I. Jerome Flance, a pulmonologist, who had a long history of advocating for underserved children. Flance was in his 80s when he embarked on a major fundraising effort with Baron (the center cost $11 million) and he died at age 98 before construction began.

But there it is now: the I. Jerome and Rosemary Flance Early Learning Center, a state-of-the-art facility for infants and toddlers in the neighborhood and across the area. It opened June 2, last year. It now serves 63 children from across the area and is licensed to accept 154. The center is moving methodically to insure a good mix of families from a variety of income groups.

“Part of what I wanted to do with the Vashon Compact was to start kids age 0 to 4, and prepare them for kindergarten,” Baron told me. “It’s very clear from data that early education is a very important part of a child’s life. It’s part of something that I’ve always wanted to do.”

The center approaches family and children holistically, focusing on “psychodynamic development, early language and literacy, and values and character.” It’s not just the kids who are learning lessons; it’s the parents as well. The center has a lot of special aspects, but one that stands out is healthy eating. The center has a kitchen where children can watch how their breakfasts and lunches are prepared. It is also working with the Metropolitan Sewer District to create an irrigation and rainwater system that will feed a garden that the children can explore. In just a year, the center claims to have improved literacy scores by nearly 20 percentage points for the children considered most at risk.

It will take some time before we know whether children at that center will thrive and prosper; whether they will graduate from high school, go on to college, find jobs and raise strong families. Maybe one of those kids will write Part III about Jefferson School in 15 or 20 years to let you know how it all turned out.

Great cities need people like Richard Baron who ask people of means to focus on what matters most in our community. But if there’s one thing I learned over my 18 months of research it’s that there’s no substitute for teachers like Mary Spencer, nor for parents like mine and those of my friends.

Children need to know that everyone is willing to step up to support and love them.

And when they do, they will love us back.

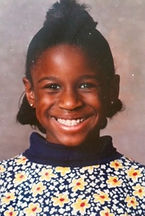

Evita Caldwell, all grown up, and back in the day.

Howard Small was a handful as a fifth grader, but he was an avid reader. R.L. Stine and J.K. Rowling captured his attention.

Howard with his daughter Brayana at his apartment in St. Charles.

Mary Spencer at home in University City. Spencer is nearly unique, having taught 41 years at the same school.

Kiauna Jones as a fifth grader. After leaving Jefferson School, Kiauna transferred to the Rockwood School district under the desegregation program, which required an hour on the bus each way.

Kiauna with her son, Ayden Manuel.

Richard Baron discussing plans for projects in underserved communities nationwide.

Raymond Webber with his baby girl, Kylee Rae, and his other daughter, Jada. At right is his girlfriend, Alica Duncan.

Raymond's mother, Lisa Ross, with Evita Caldwell. Each of her children have college degrees.

Bre' Ann Jones Johnson went to Rockhurst University in Kansas City, but returned home to St. Louis where she got married in a church across the street from Jefferson School. She now lives with her husband in the Penrose neighborhood nearby.

Ashley Westbrook (right) with her good friend Evita Caldwell reflecting on old times at Jefferson School.

Jefferson students have improved their academic performance since Nathalie Henderson became principal in 2009. This was her last year at the school.

Richard Baron had dreamed of putting an early childcare center near Jefferson School for more than 15 years. Last year, his dream came true when the I. Jerome and Rosemary Flance Early Learning Center opened in the Murphy Park neighborhood.